Drops of Water Wear out the Stone

Small Efforts, Grand Results —Lou Zhenggang’s Recent Paintings

Shimbata Yasuhide

The priest searched meticulously, up in the blue beyond and down in the Yellow Springs below the earth, but could not find her in either vast world.

Bai Juyi, Song of Everlasting Regret

I will, someday, become accustomed to drawing white lines on a white canvas and blue lines on a blue canvas. White lines in the space that is a white canvas exist yet dissolve into space. I hope someday to reach that state of mind.

Lou Zhenggang, Kokoro[1]

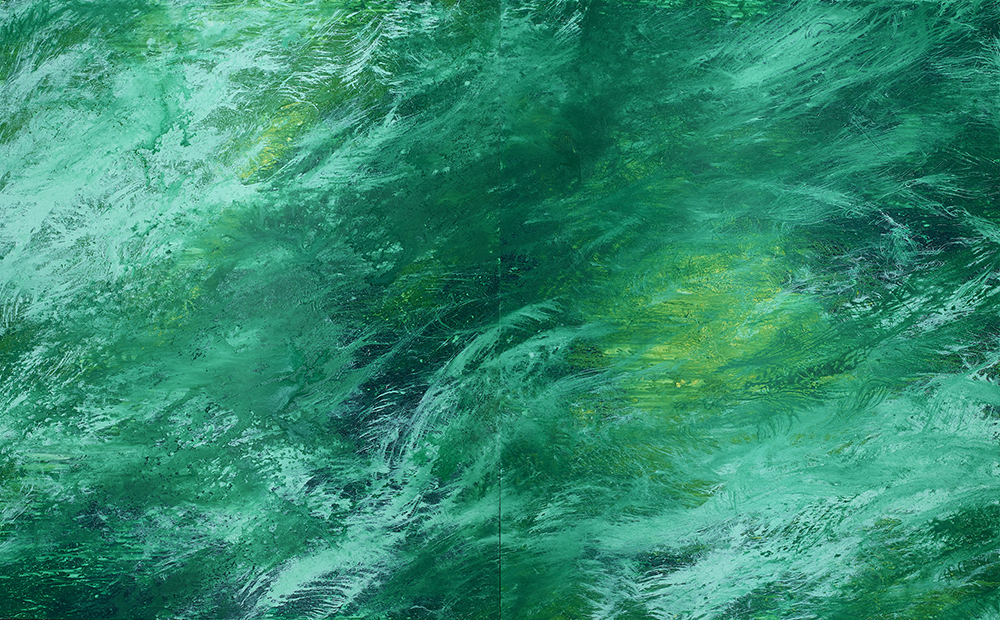

Untitled 2021 Acrylic on canvas 162.0cm×260.0cm(diptyque)

1.

Looking at the group of works before my eyes, I gasped. Painted on large and small canvases were acrylic pigments with bright white on a dark ground as the base note, images delicate yet full of vigor, flowing, leaping, dripping, surging. These paintings, composed of colors and depths created with transcendent brushwork, have a quality unlike abstract paintings from Japan or the West.

Having been introduced to Lou Zhenggang’s atelier by Takeyasu Kikuchi, I saw her paintings for the first time on September 18, 2020, in the midst of the pandemic, in an artist’s viewing room in Hirakawa-cho, Chiyoda City, Tokyo. I had received this email message from Kikuchi saying that he wanted to introduce an artist, earlier, on May 28:

Lou Zhenggang studied calligraphy and painting in China with her father from early childhood. She came to Japan in 1986, when she was twenty. Since then, with Japan as her base, she has had twenty-seven solo exhibitions in venues throughout the world and three traveling exhibitions. At present, she is energetically painting in her atelier in Izu. . . . I always have work by her on display in my studio and hope you will come to see them.

I later learned that that invitation was inspired by the 2011 Postwar Abstract Paintings in France and Art Informel exhibition at the Bridgestone Museum of Art, which I had planned. That exhibition focused on the abstract art that flourished in Paris after World War II, known as hot abstract painting or, in Japan, Art Informel.[2] Hot abstraction was a term often used in Europe after World War II and particularly in France in the first half of the 1950s. After the war, the abstract art movement had spread internationally, involving the United States as well, and artists in France felt it necessary to separate its tradition of pure abstraction from the newly emerging Abstract Expressionism. Pure abstraction, composed of geometric forms and a limited palette, as exemplified by Mondrian, was called “cold abstraction” and was distinguished from the “hot abstraction” found in abstract paintings by artists such as Jean Dubuffet and Wols and in the dynamic compositions, free use of color, and violent actions of Jackson Pollock or Willem de Kooning. These trends promptly spread to Japan, where the Gutai Art Association and others promoted abstract painting. Lou Zhenggang’s paintings share an extraordinary boldness and delicacy with the works of those artists. Yet hers have something about them, a quality that draws a line between her work and theirs. That quality, one senses, arises from the artist’s sensibility and exceptional skill.

2.

Lou Zhenggang was born and raised in northern China, in Xiaohenshan, a coal mine town, in Heilongjiang Province, near the border with Russia. The temperatures there fell to thirty or forty degrees centigrade below zero in the winter, and it was visited by towering accumulations of snow.[3] The artist has said of her childhood memories of that place, “Nothing remains in my heart but an impression of white and black, all year long.” She was born on July 8, 1966, a month before the Great Cultural Revolution began. Her father, Lou Deping, did public relations work associated with the Xiaohenshan Coal Mine’s advertising department. We are told that at times, he wrote slogans to stir up the people with his skillful brush. Lou Zhenggang was already using the brush at the age of three, having fun painting with sumi ink. Her father’s influence was apparently great in the early emergence of her abilities, for, apart from his official position, his true calling was as a poet and calligrapher. When she was five, she wrote chunlian, auspicious couplets in black ink on red paper to decorate doorway at the entrance to a building, to welcome the new year, in place of her terribly busy father. Seeing how superb her work was, her father became certain of his child’s talent and pledged that from then on he would guide Zhenggang strictly and help her enhance her calligraphy. Immediately after the announcement of the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1977, the government implemented a national gifted education program for especially talented children. Zhenggang’s talent for calligraphy and her intelligence were recognized, and she was able to study calligraphy and painting at the Central Academy of Fine Arts. Her activities drew notice, and her work was acquired for the collections of the National Museum of China, the Palace Museum, and other institutions. In 1979, her kaishu (Japanese: kaisho, “formal script”) calligraphy shown at an exhibition of calligraphy, painting, and seal engraving organized by Heilongjiang Province attracted great attention. As a result, she was able to go on a tour with her father to visit famous calligraphers throughout China and ask for their instruction.

During that tour, the Lou father and daughter visited the Rong Bao Zhai, a painting and calligraphy supplies shop that has operated for more than three centuries in Beijing. There they happened to meet a group of leading Japanese calligraphers, and Zhenggang gave a demonstration of her calligraphy. The Japanese visitors were amazed and praised her to the skies. She continues to cherish the memory of that experience. It made her certain, she has said, that if she were ever able to go to another country, the country she would hope to visit was the one where, so early in her work as a calligrapher, her abilities were so purely recognized. Indeed, in July, 1986, Lou Zhenggang traveled from Beijing to Japan, via Hong Kong. There she continued to develop her work steadily, in contrast to the uncertainty that might have been expected of a very young woman, barely twenty years old. In 1987, she had a solo exhibition at the Yaesu Gallery in Tokyo. The Lou Zhenggang Works exhibition, organized by TV Tokyo and sponsored by the Embassy of China in Japan and Nikkei (the Nihon Keizai Shimbun-sha), was held to celebrate the fifth anniversary of the opening of the Sogo Yokohama department store. She was remarkably active during her time in Japan, and her dazzling career as a calligrapher in Japan and China included too many achievements to mention. Her activities then crossed the Pacific Ocean as well.

Lou Zhenggang made the United States her base from 1993 to 2000. The immediate inspiration for that move was her need for a change in mood, after six years of working in Japan, in order to take her next step. After a stay at Pebble Beach, on California’s Monterey Peninsula, that included a vacation with her mother and younger sisters, she made New York her base for seven years. She set up her residence in a high-rise building that looked directly down on the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) on 53rd Street in midtown Manhattan. Lou Zhenggang began her serious work in the atelier that she set up there and also visited the museum frequently. She already had a strong interest in modern Western art and, on trips to Europe, had frequently visited museums and passionately studied and absorbed modern and contemporary European art. When I asked her what particularly impressed her at MoMA, she mentioned Abstract Expressionists such as Jackson Pollock and Joan Mitchell.

Was it then, I asked, that she shifted her emphasis from calligraphy to painting? Her expression suggested she had been caught off guard. But, she said, from early childhood, her own interest had always been in both calligraphy and painting, and that remained unchanged. Indeed, Lou Zhenggang is not just a calligrapher but a calligrapher and painter. That extremely important point must not be forgotten when we attempt to understand her work. In contemporary Japan, with the overlaying of the Western modern artist historical context, it is undeniable that many among artists would hesitate to address calligraphy and painting as equals. Lou Zhenggang has, however, treated them as inseparable, from her childhood, and she continues to this day to create both paintings and calligraphic works. Many are in a figurative style that is related to ink wash painting, with its long history in China.

3.

In China (and Japan), paintings have, from long in the past, had deep connections with both literature and calligraphy. Poems and other texts related to a painting’s contents are often written on the negative space of landscape paintings or the ends of picture scrolls. From a Western perspective, the poem or text added to a painting would be understand as supplementing what is being expressed by the painting. Traditional East Asian paintings, however, have a different historical and cultural context. In China, poetry, calligraphy, and painting are termed the “Three Perfections.” The ideal cultured individual would have a mastery of each of those arts. Similarly, in Chinese thought, shu-hua yi-zhi-lun, “calligraphy and painting are one.” The art of painting, which developed from the Tang period (618-907) on, has been regarded as equal to calligraphy, the artistic value of which had been established during the Six Dynasties period (220-589). In the Tang, Zhang Yanyuan’s Fashu Laolu (Compendium of calligraphy) states that the origins of the written word and paintings are the same, because the same brush (techniques make possible expressing the artist’s inner world.[4]

That traditional way of thinking about painting had long been maintained in Japan as well. Right after World War II, however, calligraphers who had been seeking new styles in the world of calligraphy, and carrying on the avant-garde trends from the prewar period, began working towards radical reforms. They began a movement to free calligraphy from the “written word.” The resulting works were appearing at the same time as the rise of Abstract Expressionist painting in Europe. The same potential as a visual art was discovered in works created with flowing and powerful brushwork similar to calligraphy. Those postwar progressive calligraphers included the members of the avant-garde calligraphy group Bokujinkai (People of the ink), including Morita Shiryu, Inoue Yuichi, Eguchi Sogen, Sekiya Yoshimichi, and Nakamura Bokushi—and Sonoda Toko, who was born in Dalian, China, first encountered ink and brush, under her father’s guidance, at the age of five, taught herself calligraphy, and dissected Chinese characters to develop an abstract style in ink.[5]

Meanwhile, interest in the art of calligraphy was rising among abstract painters in Europe and America, inspired by calligraphy’s action nature and free lines. Franz Klein, who had a relationship with Morita Shiryu, was a leading example. He had close ties with the Gutai Art Association in its early period and with the Bokujinkai. Pierre Soulages, who drove the abstract painting movement in postwar France and whose style is characterized by broad black brushwork, was developing paintings that seemed close to calligraphy. Soulages came to Japan in 1958 and had opportunities to meet Morita Shiryu and others.[6] And traveling with Soulages from Paris to Japan was Zao Wou-ki, a painter of Chinese origins. Zao was born in Beijing in 1921. After graduating from the Hangzhou School of Fine Arts, he joined its faculty. But, unable to give up his love of modern French painting, which he had learned of through books of paintings, he gave up that position to seek new terrain, moving to France in 1948. Having begun to paint there, Zao Wou-ki was soon recognized by the Belgian-born French poet Henri Michaux and began to distinguish himself in the postwar Parisian art world. He mastered the essence of European modernism in painting and, in particular, through encountering Paul Klee, learned methods of expressing his sensibility and interior world and became determined to create his own style of painting. In the abstract painting boom that emerged in the early 1950s, he threw himself into the activities of the hot abstract artists, who were seeking an expressionist approach. In time, he brought his own painting style to maturity. Those works, while based on developments in avant-garde art in the West, were noted for their sense of continuity with an Eastern creative tradition.

Zao’s taking nature itself as a source of inspiration, his rich use of color and space with great depth, his brushwork with its sense of speed, compositions that combine magnificence and freedom—by and large his work is the classic example of hot abstraction in postwar France, yet has a quality that transcends that scheme.

While Lou Zhenggang differs from Zao Wou-ki in both time and place, she too, after having earned a name as a calligrapher and painter, studied modern Western art extensively, and as a painter was equipped with distinctive skills and abilities that were decisively different from the techniques and styles of Western art. To describe her work as a fusion of Eastern and Western traditional cultures is overly simplistic. Similarly, To understand and position her art in the context of contemporary art without grasping that historical and regional background appropriately is not possible. Zao Wou-ki is, as an important predecessor, a valuable reference for understanding Lou Zhenggang’s art, but their work and the nature of their art are utterly different. They also differ in their engagement with the art world. After Lou Zhenggang came to Japan, she interacted with avant-garde artists here but was never involved with an individual artist or a specific art group or movement. That she has always developed her art independently is an important factor in understanding her work.

4.

Lou Zhenggang left the United States in 1997, then lived in Tokyo until 2008, in Beijing until 2015, and once again in Tokyo until 2017. From her first visit to Japan on, she frequently visited Europe and America, saw many paintings in the West, and was blessed with opportunities to consider what a painting is and what she should do. Viewing the nature of contemporary art, with all its drastic changes, she may have sought to express the artistic value that welled forth from within herself, without just adhering to tradition and without being confused. She switched from painting in sumi ink to acrylics, replaced paper with canvas as her substrate, gradually increased the size of her paintings, and enhanced the nature of her paintings to the utmost. It is easy to seek the source of those changes in Song or Yuan or Abstract Expressionist painting, and they may have indeed triggered the paintings she has been creating recently. But if one listens carefully to what Lou Zhenggang herself says, those were no more than sources of occasions for creating. She has indeed made full use of her extraordinary abilities as a contemporary artist, but she has transformed them in many ways for use in creating new paintings. To achieve new artistic creations, Lou Zhenggang dislikes being tempted by the influences of her surrounding. To position her questions as those of an artist as an individual and to build her own style in solitude, she left Tokyo and moved to Hakone in 2018 and then to Izu, where she has had her atelier since 2019. There, undisturbed by unwanted distractions, she spends her days concentrating on her work.

Invited by Kikuchi, I had the opportunity to visit Lou Zhenggang’s atelier in Izu on April 2, 2021. From her large atelier, Sagami Bay spreads below, with Oshima Island visible in the distance; the atelier is surrounded by a lush green natural environment. The artist spends all year there, in the daytime raising roses and other plants in her garden and growing vegetables in her field. In the evening, she applies herself to her work and nothing else, staying up all night. That, she says, is how she spends her days. Weekends, holidays are irrelevant—she keeps on working without a break. The number of paintings she has created in the past few years is huge. Surprisingly, the majority have yet to be exhibited. While these individual works are painted in a style that the artist herself has perfected, none of them are painted in the same way. It is clear at a glance that she is constantly exploring new modes of expression.

Lou Zhenggang at present is freed from all matters that once constrained her. Relying entirely on her own perceptions and thinking, she keeps on painting pictures as her heart dictates. Showing the work that she is endlessly creating or having it evaluated by someone are not part of her thinking. With a view of the sea and in a landscape surrounded by mountains, she keeps on painting, alone, and expresses her strong intention to spend the rest of her life engaged only in creative work. She is provoked by the desire to create, to produce works that will embody pure artistic value, without adhering to painting and calligraphic traditions. The outstanding techniques that she has been trained in, again and again, since childhood are fuel for her efforts, but she wields her brush as she pleases, unconstrained by the rules of those disciplines.

Considering this artist’s stance, another painter comes to mind. He began as a member of the Impressionist group in fin de siècle Paris, but gradually placed a distance between himself and those colleagues, then moved far away from the capital, to Aix-en-Provence: Paul Cézanne. In the long years after that move, he sought to go beyond Impressionism, to create paintings with a solid sense of mass and a tenacity that would survive forever. Since that body of work was discovered early in the twentieth century, its true value has been recognized. Proudly independent painters are like that, but artists who elevate their art, in solitude, with that tenacious spirt, and their work, were rare presences among his contemporaries.[7]

“Small efforts, grand results” (shuǐ dī shí chuān: literally, “drops of water wear a hole in stone”) has been Lou Zhenggang’s motto since childhood, she has said. This painter has and will transform her work in many ways throughout a long career, but her attitude towards creating has remained unchanged. To execute the mission that she has imposed on herself, again and again, she has kept on painting. Now and throughout her career, she has developed a new art of painting, day by day. Her work continues to change and develop; where it is headed, we do not know. As the artist herself has said, “I entrust my spirit as a whole to each painting; I want to touch the spirit of the person who looks at my work. I want to keep painting, to the very limits of my self control, without collapsing.”[8] This book is a collection created to introduce the paintings that Lou Zhenggang, now flourishing in the twenty-first century, continues to produce, with the hope that many will have opportunities to encounter these works.

Shimbata Yasuhide

Chief Curator

Artizon Museum, Ishibashi Foundation

- [1] These two quotations are both from Kokoro, by Lou Zhenggang (Sekai Bunka-sha, 2001). The lines from mid-Tang-period poet Bai Juyi’s Song of Everlasting Regret Lou quoted in the last chapter of that rather autobiographical book, where she states that “It expresses my feelings about my art now” (p. 269). The quotation from Lou can be found at the end of the eighth chapter (p. 260).

- [2] Postwar Abstract Paintings in France and Art Informel, Bridgestone Museum of Art, Ishibashi Foundation 2011.

- [3] The information on Lou Zhenggang’s personal history and career in this essay is based on the author’s interview with the artist, Lou Zhenggang’s book Kokoro (Sekai Bunka-sha, 2001), and Zhang Baoqing, “Painting under heaven, a member of the global art world—on Lou Zhenggang’s paintings,” in Lou Zhenggang 2010: Sun and Moon, 2009. The quotation from “Pacified Waves and Storm” by Su Shi was chosen by Lou Zhenggang for the last chapter of this book.

- [4] “Calligraphy and painting are one [Shoga itchi ron].” Shincho sekai bijitsu jiten [Shincho world dictionary of art], Shinchosha, 1085, p. 719; Zhang Yanyaung, Nagahiro Toshio, tr., Rekidai meiga ki [Famous paintings through the ages], (Toyo Bunko 305, 306), Heibonsha, 1997.

- [5] Hariu Ichiro, “Sengo no zen’ei sho—Kaiga to no mitsugetsu jidai wo koete [Avant-garde calligraphy after the war: beyond the honeymoon with painting]”; Amano Kazuo, Introduction, from catalogue for Sho to kaiga no atsukijidai: 1945-1968 [Hot times for calligraphy and painting: 1945-1969], O Museum, 1992, pp. 2-5, 6-14.

- [6] Shimbata Yasuhide, “Pierre Soulages to Nihon [Pierre Solages and Japan],” form catalogue for Soulages to Nihon [Soulanges and Japan], Galerie Perrotin, 2017, pp. 87-99.

- [7] Shimbata Yasuhide, “Sezanu raisen—20 seiki kaiga he no eikyo to tenkai [Homage to Cezanne: His influence on the development of twentieth century painting], exhibition catalogue for Homage to Cezanne: His Influence on the Development of Twentieth Century Painting, Yokohama Museum of Art, Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art, 2008, pp. 11-15.

- [8] Lou Zhenggang, Kokoro, Sekai Bunka-sha, 2001, pp. 40, 269.